|

Project #2: Group 17

The Jefferson Memorial & The Pantheon : Symbols of Democracy

Gretchen Rodriguez

Christy Fant

Traevon D. Jones

Kathryn Crowell

Jordan Marthaler

The Jefferson Memorial, created due to a congressional act of 1934, took nearly four years to complete construction.

This was mainly due to the controversy surrounding the architecture of the building. The use of classical style Roman architecture

in Washington D.C. was thought to be too exhausted. Also, the design was thought to be too similar to the Lincoln Memorial

and a more original plan for the structure was suggested. President Roosevelt eventually made the final decision to proceed

with the memorial in the Pantheon style. Therefore, the design of the memorial was adapted to Jefferson's repeatedly demonstrated

preference for Roman architecture. Although the Pantheon was used as the inspiration for this memorial, there are a few noteworthy

differences that allow the memorial to stand as its own great construction, not just a simple reproduction. (www.glasssteelandstone.com)

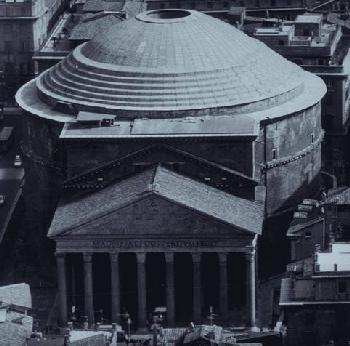

Just like the Pantheon, the Jefferson Memorial contains an immense 129 foot dome that is 4 feet thick. The dome of the

Pantheon is slightly larger, however, at 143 feet high and 6 to 20 feet thick, spanning 142 feet. It is constructed of stepped

rings of solid concrete with less and less density as lighter aggregate is used, diminishing in thickness at the edge of the

oculus. Both structures have constructed the dome and drum carefully, with the diameter of the floor of the drum equaling

the height of the dome, to ensure perfect balance and stability.

The Pantheon has an expansive portico currently facing the Piazza della Rotonda and is entered through impressive bronze

doors leading to a large circular room. This porch consists of three rows of eight columns 46 feet high, constructed of Egyptian

granite with Corinthian capitals. By comparison, the Jefferson Memorial's porch is made up of triple rows of Vermont marble

colonnades and a 25 foot high podium. The Pantheon's interior space is cylindrical, on account of the drum covered by the

aforementioned dome. Under the dome pairs of columns rise above a series of recessed apse, patterned alternately rectangular

and semicircular. In this way, the space is less a solid mass and more like three continuous arcades that correspond to the

three tiers of arches seen on the building's exterior. The interior space of the Jefferson Memorial is quite similar to the

Pantheon in these respects, although the result does not draw as much focus on the interior space but rather the exterior.

The Pantheon is lighted only naturally, through an oculus in the center of the dome as well as the bronze doors of the

entrance. This light serves to illuminate the interior granite and yellow marble in different arresting patterns throughout

the various times of the day. Meanwhile, the Jefferson Memorial has no oculus and instead light enters though the open cella.

(Bedford and Goode)

The architecture of the Jefferson Memorial contains several elements that serve to both symbolize the United States' democratic

ideals and pay tribute to the ancient culture of Rome. Author of the Declaration of Independence, founding father of the

United States, and third president, Thomas Jefferson was a strong supporter of democracy and admirer of Roman culture and

architecture. As such, only a monument in the Roman classical style would best honor him. The memorial's basic construction

is strikingly similar to the Pantheon, with an impressive porch with columns, drum, and massive dome. Although a brief description

of this structure seems odd with its combination of a cubic porch and globular dome, the resulting building was actually architecturally

a perfect, aesthetic balance. Metaphorically, the United States, a democratic country constituted of a medley of people who

are united under one government, achieve the same balance.

Furthermore, the grandeur of both the memorial and the Pantheon required extreme precision for solid construction, particularly

to support the colossal weight of the dome. This could only be achieved after much careful planning and design as well as

consideration of other earlier, similar structures. In Rome, thermae were thoroughly examined for the building of the Pantheon

and, subsequently, the Pantheon was scrutinized for the construction of the Jefferson Memorial. However, the memorial is

not a complete replica of the Pantheon, instead it has its own characteristics while paying tribute to the Roman original.

A close parallel can be drawn regarding the American ideal of a strong foundation in democratic government that unfailingly

supports and protects the people. This foundation, being created by a respected group of individuals who meticulously considered

earlier forms of government, ultimately resulted in the formation of the current unique American democracy that does not duplicate

other forms of government but found a basis in them from which to grow and develop.

Finally, attention must be given to the interior of both buildings as well as their respective dedications. The Pantheon,

dedicated to the planetary gods, contained sculptures in their likeness. Likewise, the Jefferson Memorial contains a bronze

statue of the ex-president, by Rudolph Evans, and another sculpture showing members of the committee that drafted the Declaration

of Independence. Additionally, a number of his most well known quotations line the walls memorializing his timeless wisdom.

In the end, with its likeness to the Pantheon, the Jefferson Memorial now represents that which the Pantheon has represented

for some time, democracy and enlightenment.

References

Bedford, Steven McLeod, John Russell Pope: Architect of Empire, Rizzoli

International Publications, Inc., New York, NY 1998

Blaser, Werner and Monica Struck. Drawings of Great Buildings. Boston:

Birkhauser Verlag, 1983.

Goode, James M. The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington D.C., Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington D.C. 1974

James Stevens Curl. Classical Architecture: an introduction to its vocabulary and essentials, with a select glossary of

terms. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1992.

|